The last time the US Supreme Court considered whether a creative work qualifies as a transformative use under the Copyright Act was nearly 30 years ago, in Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc. In the Campbell decision, the Court stated that the central inquiry of transformative use is “whether the new work merely supersede[s] the objects of the original creation, or instead adds something new, with a further purpose or different character, altering the first with new expression, meaning, or message.” Since then, lower courts have assessed whether a use is transformative by focusing on the latter part of the Court’s articulated inquiry: whether “new expression, meaning, or message” has been added to the original copyrighted work.

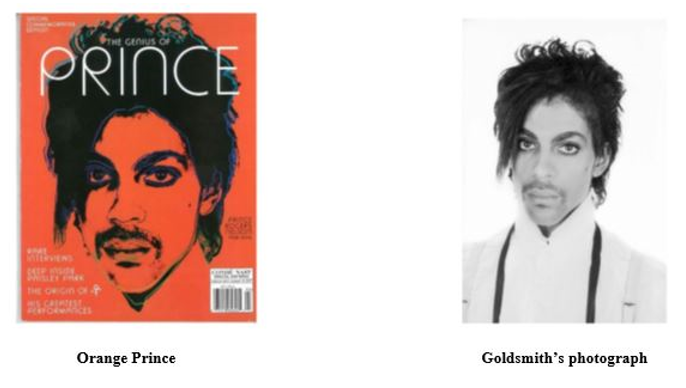

On May 18, 2023, the Court issued its long-awaited decision in The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith. In a 7-2 ruling, the Court affirmed the Second Circuit’s decision that AWF’s licensing of Warhol’s “Orange Prince” in 2016 for use on a commemorative edition magazine cover (below, left) does not constitute fair use of Goldsmith’s copyrighted photograph of Prince (below, right).

The court’s decision

In an opinion written by Justice Sotomayor, and joined by Justices Thomas, Alito, Gorsuch, Kavanaugh, Barrett, and Jackson, the majority held that the purpose and character of AWF’s licensing of Orange Prince in 2016 were not transformative and therefore do not favor a fair use defense to copyright infringement because it served substantially the same purpose as that of Goldsmith’s copyrighted work: “to illustrate stories about Prince.” The majority also noted that the commercial nature of AWF’s licensing of Orange Prince in 2016, though not dispositive, “tends to weigh against a finding of fair use.”

The majority limited its analysis of whether AWF’s use was transformative to AWF’s licensing of Orange Prince in 2016; it expressed no opinion on the purpose and character of the creation of the original Prince Series works, or its display in a 1984 issue of Vanity Fair, which were done pursuant to a license from Goldsmith.

The majority rejected AWF’s position that Orange Prince’s use of the copyrighted work is transformative in the fair use sense because it adds new meaning or message—namely, a comment on “the dehumanizing nature of celebrity.”

Justice Gorsuch, in a concurring opinion joined by Justice Jackson, rejected AWF’s position primarily because it would force “judges to speculate about the purpose an artist may have in mind when working on a particular project,” or “try their hand at art criticism….” The concurring opinion also attempted to cabin the effects of the majority opinion on other uses of Orange Prince, noting that displaying it in a nonprofit museum or even a for-profit book for the purpose of “commenting on 20th-century art…might well point to fair use.”

In a dissenting opinion, Justice Kagan, joined by Chief Justice Roberts, argued that assessing transformative use should focus on whether the work in question “adds something new, with a further purpose or different character, altering the [original] with new expression, meaning, or message.” The dissent concluded with a grave repudiation of the majority for recasting the first-factor inquiry in a way that “will stifle creativity” and “make our world poorer.”

Practical takeaways

How well the claims of the majority and dissent will age remains unknown. However, the art community now has the task of reconciling the Court’s clarified test for transformative use. Artists will need to contemplate the respective purposes served by the inspired new work and the copyrighted work, and whether those purposes are substantially the same. Or, to avoid that issue altogether, artists may want to obtain the appropriate licenses before creating new works that incorporate copyrighted works.

As for art galleries and museums, their ability to display Warhol works or other artistic works that incorporate prior copyrighted works will likely not be impacted adversely by the decision. Presumably, those artistic works are displayed for purposes like depicting an artist’s particular painting style or showing how the particular work fits in a particular movement in art history. Such uses would likely be deemed transformative under the Court’s articulated test.

Written by Ivy Estoesta, Director, Sterne, Kessler, Goldstein & Fox PLLC.