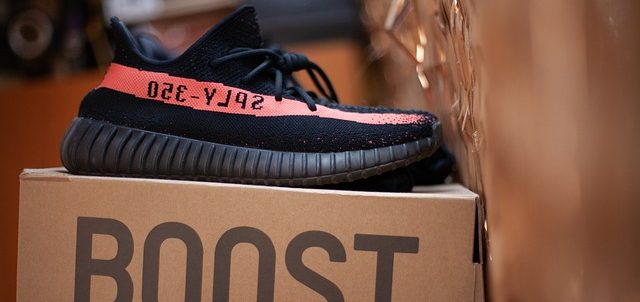

After severing its wildly successful Adidas Yeezy partnership with artist and rapper Ye, formerly known as “Kanye West,” Adidas announced that it will no longer produce Yeezy branded products, including the popular Adidas Yeezy sneakers. Adidas has expressly stated that it will, however, continue to produce and sell sneakers based on existing Yeezy designs without the Yeezy trademarks. According to Adidas, such action is permitted because it is the sole owner of all design rights to existing products and previous and new colorways under the partnership.

After severing its wildly successful Adidas Yeezy partnership with artist and rapper Ye, formerly known as “Kanye West,” Adidas announced that it will no longer produce Yeezy branded products, including the popular Adidas Yeezy sneakers. Adidas has expressly stated that it will, however, continue to produce and sell sneakers based on existing Yeezy designs without the Yeezy trademarks. According to Adidas, such action is permitted because it is the sole owner of all design rights to existing products and previous and new colorways under the partnership.

While the content of the agreement between Ye and Adidas is not public, Adidas’s decision raises the question: Can existing Adidas Yeezy sneakers be customized, or new designs, with the look and feel of the existing Adidas Yeezy sneakers, be created without running afoul of Adidas’s intellectual property (IP) rights? The answer may depend, in part, on whether the new shoes are “expressive works.”

Sneaker designers and other artists regularly customize existing sneaker designs or create new shoes with the look and feel of existing sneaker designs for purposes of social commentary or parody. For example, in 2008, artist Jimm Lasser took a pair of Nike Air Force One sneakers and transformed them into a commemorative sculpture to mark the election of President Obama. Further, in reaction to the extremely limited release of the Nike Mag shoe, sneaker customizer Nicholas Avery made a pair of “Fuck Mags” sneakers to “capture the feelings of true sneaker heads at that time.”

In today’s sneaker-obsessed culture, questions have arisen regarding how far artists and sneaker customizers can push the boundaries of sneaker design before one’s artistic expression becomes an IP offense. For example, Vans, Inc. and VF Outdoor, Inc. (“Vans”) sued MSCHF Product Studio (“MSCHF”) for designing and selling a shoe called Wavy Baby in collaboration with rapper Tyga. MSCHF describes the shoe as a “work of art” and an “expressive work” protected by the First Amendment, but Vans claims the shoe is a classic case of trademark infringement. Vans, Inc., VF Outdoors LLC v. MSCHF Product Studio, Inc., 22-606-cv (2d Cir.). Current IP laws provide some guidance, but leave unanswered questions on where the appropriate line should be drawn.

In Rogers v. Grimaldi, 875 F.2d 994 (2d Cir. 1989), the Second Circuit found that an artistically expressive use of another’s trademark may be protected by the First Amendment, and therefore will not constitute trademark infringement unless the use of the trademark “has no artistic relevance to the underlying work whatsoever, or, if it has some artistic relevance, unless the [use of the trademark] explicitly misleads as to the source or the content of the work.” 875 F.2d at 999. The Ninth Circuit has concluded that a work is expressive where it “is communicating ideas or expressing points of view.” Mattel, Inc. v. MCA Records, Inc., 296 F.3d 894, 900 (9th Cir. 2002).

While copyright does not protect useful articles such as sneakers, Adidas successfully obtained copyright registrations for design elements of two versions of Adidas Yeezy sneakers produced under the parties’ collaboration. To the extent a new design substantially transforms these original works, such that it “add[s] something new, with a further purpose or different character, altering the first with new expression, meaning or message,” the use may be deemed a “fair use,” an affirmative defense to claims of copyright infringement where copyrighted works are used for purposes of “criticism” or “comment,” among other purposes. Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc., 510 U.S. 569, 576, 579 (1994); 17 U.S.C. § 107.

In assessing design patent infringement, the addition of logos and artistic expression on new designs could limit liability for infringement. The Federal Circuit has held that an accused infringer’s ornamental logos, and their placement and appearance, can be considered when assessing whether infringement has occurred. See Columbia Sportswear North America, Inc. v. Seirus Innovative Accessories, Inc., 942 F.3d 1119 (Fed. Cir. 2019). The Federal Circuit stated that the applicable test is whether an ordinary observer would find the “effect of the whole design substantially the same.” Id. at 1131.

So how will the Yeezy brand move forward? Possibly by trying to successfully transform a previously wearable form of self-expression into a new medium of artistic expression.

Disclaimer: The above should not be construed as legal advice on any specific facts or circumstances. Stroock & Stroock & Lavan LLP does not represent Ye or Adidas in any respect and is not aware of the contents of the Adidas/Ye partnership agreement.

Written by Alesha Dominique, Head of Trademark Practice at Stroock

| MORE NEWS | | SHARE NEWS WITH OUR EDITOR |