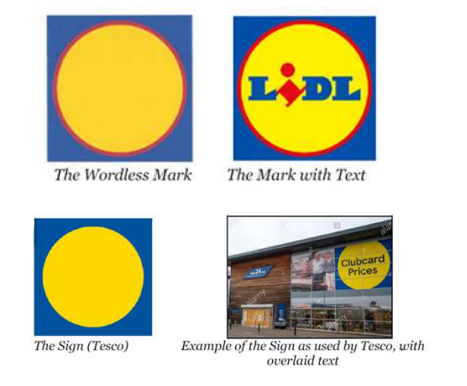

Lidl has won its claim for trademark infringement against Tesco concerning the latter’s use of a yellow circle within a blue square for its Clubcard Prices scheme. Lidl argued that such use infringed its trademark registrations for a similar logo with and without the word ‘Lidl’.

Lidl has won its claim for trademark infringement against Tesco concerning the latter’s use of a yellow circle within a blue square for its Clubcard Prices scheme. Lidl argued that such use infringed its trademark registrations for a similar logo with and without the word ‘Lidl’.

Lidl also succeeded in its claim for passing off and copyright infringement. Although Tesco was able to invalidate some of Lidl’s trademark registrations for the wordless mark on the grounds that they were applied for in bad faith, that did not change the overall outcome of the case.

Lidl’s claims

Interestingly, Lidl did not bring a likelihood of confusion-based trademark infringement claim, but a reputation-based claim.

Lidl was able to provide substantial evidence that its marks had a significant reputation for supermarket services in the UK.

The court considered that the average consumer would view Tesco’s logo as similar to Lidl’s marks. Any differences in word elements did not extinguish the strong similarity conveyed by the mark’s backgrounds.

The court concluded that the use of the Tesco logo takes unfair advantage of the fame of the Lidl logos, as Tesco benefits from the value proposition conveyed by the Lidl logos. Such use was also detrimental to the distinctive character of Lidl’s logos as it would dilute the latter’s uniqueness.

Lidl’s claim of passing off related to equivalence rather than trade origin. Lidl was able to successfully argue that a substantial number of customers would be misled to believe that the Tesco Clubcard Price was the same/lower than the Lidl price for the equivalent goods. That mistaken belief would deceive consumers and cause damage to Lidl because price sensitive shoppers would switch from Lidl to Tesco.

Lidl also won on copyright infringement. Given the degree of similarity between the logos and the fact that Tesco had access to the Lidl logos, the burden of proving lack of copying passed to Tesco. It was unable to discharge that burden, demonstrating the importance of having detailed records as to the genesis of a logo to corroborate lack of copying.

The case illustrates that brand owners must be careful not to stray too close to their competitors’ marks, even if those marks consist of seemingly commonplace and banal elements. This is particularly so where the mark is well-known. Simply adding different words to a mark might not be sufficient to avoid trademark infringement. Furthermore, when using a logo or figurative element, brand owners must also consider potential liability for copyright infringement.

Tesco’s counterclaim

Tesco counterclaimed that Lidl had no genuine intention to use its wordless marks and that they had therefore been applied for in bad faith, on two bases.

Firstly, Tesco argued that Lidl had applied for the wordless marks as a defensive weapon, solely to use against others and to widen its monopoly. Secondly, Tesco argued that Lidl had filed successive applications for the wordless marks to circumvent the rules on proving use (so-called ‘ever-greening’).

Importantly, at an earlier hearing, the Court of Appeal held that the objective circumstances raised by Tesco were sufficient to create a rebuttable presumption of lack of good faith by Lidl such that it was now for Lidl to provide a plausible explanation of its objectives and commercial logic.

Those circumstances were the combination of (i) repeat filings with (ii) the assertion that Lidl had had no intention, at the time of filing the original wordless application, of using the wordless mark and (iii) the fact that Lidl had never used the wordless mark.

Lidl was not able to explain the rationale for the repeat filings (except for a 2021 registration which therefore survived), raising a permissible inference for the court to find there had been bad faith and invalidate the registrations.

The case is consistent with previous rulings on bad faith including the EU General Court’s Monopoly ruling. What is interesting is that the burden of proof shifted to Lidl to prove good faith, which was fatal to Lidl and might well be to others who have no records to justify why a particular trademark application was filed.

Written by Louise Popple, Senior Counsel – Knowledge, Taylor Wessing.