In an important decision for trademark owners and practitioners, issued by the Court of Appeal on 2 November 2022 in Lidl Great Britain Ltd. v. Tesco Stores Ltd., Tesco has been permitted to continue to argue at trial that a wordless version of Lidl’s logo was periodically filed and refiled by Lidl in bad faith. The Court of Appeal overturned the High Court decision, which had previously disallowed Tesco’s allegations of bad faith.

In an important decision for trademark owners and practitioners, issued by the Court of Appeal on 2 November 2022 in Lidl Great Britain Ltd. v. Tesco Stores Ltd., Tesco has been permitted to continue to argue at trial that a wordless version of Lidl’s logo was periodically filed and refiled by Lidl in bad faith. The Court of Appeal overturned the High Court decision, which had previously disallowed Tesco’s allegations of bad faith.

This article looks at this in more detail and focuses on its implications.

Background

The claim concerned Tesco’s Clubcard Prices loyalty discount scheme, which launched in September 2020, and offers point-of-sale discounts on selected items to Clubcard members. Two different versions of the sign as used, one with a complete circle, the other with a cropped circle, are shown below:

Lidl claims that this sign used by Tesco constitutes infringement of its intellectual property rights, based on it allegedly being similar to the background to Lidl’s logo (which uses a blue square and yellow circle with a thin red border around it).

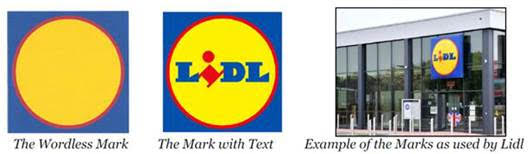

The registered mark shown below center (“The Mark with Text”) is Lidl’s well-known logo, which has been used in the UK for many years, for example as shown below right. For the purposes of this decision, however, the most important registered mark owned by Lidl is that shown below left (“The Wordless Mark”).

Tesco deny the allegation and have counterclaimed for invalidity and revocation of Lidl’s registrations of its Wordless Mark, which has never been used in the UK in the form in which it was registered, on a number of grounds, including bad faith trademark filing.

Rather, it has only ever been used as the background of the Mark with Text. Lidl contends that, as a matter of law, the use of the Mark with Text constitutes use of the Wordless Mark, in accordance with the principle laid down in Specsavers International Healthcare Ltd v. Asda Stores Ltd. in 2014[2] .

That is disputed by Tesco, who has counterclaimed for revocation for non-use, but that counterclaim is a matter for the trial and was not in issue in this interim decision.

Tesco had two principal arguments underpinning its allegations of Lidl’s bad faith filing. First, the fact that Lidl had never used, in the UK, the wordless mark in the form in which it was registered, 27 years since they had first applied for it.

Tesco alleged that the mark was on the Register purely to extend Lidl’s monopoly right beyond the mark it actually used, so as to use the extended right against third parties as a weapon in legal proceedings.

As such Tesco alleged that it was a ‘defensive mark’. Secondly, Tesco argued that Lidl, in order to avoid the “non-use” provisions (a rule that says that marks that have not been used for five years can be revoked), had kept reapplying for the mark periodically since then (an allegation of “evergreening”).

Lidl argued that there were a number of entirely legitimate reasons it might have applied for the Wordless Marks, and that Tesco had not provided a sufficient basis for its claim of bad faith to justify requiring Lidl to explain its actual reason(s) for applying for the Wordless Mark registrations, whether by providing disclosure and evidence in relation to its filing strategy, or otherwise. The Court of Appeal however decided that Tesco’s claim had ‘a real prospect of success’.

The case comes hot on the heels of the UK Supreme Court agreeing to hear Skykick’s appeal in Sky v. Skykick in 2021, which had rejected Skykick’s allegations of bad faith and restored Sky’s UK registrations.[3]

Skykick’s arguments, rejected by the Court of Appeal in July 2021, had been that Sky’s trademark registrations were invalid for bad faith to the extent that they covered goods and services in relation to which Sky had no intention of using the marks.

Both the Tesco case and Skykick are defensive marks cases, in the author’s opinion. Sky has a thriving, multi-faceted business and is clearly entitled to broad protection; Lidl the same. But so broad that they can apply for things beyond the edges of their actual trade, thereby extending their protection ever outwards?

In the author’s opinion, Sky does so by extending the goods or services, and for Lidl it is by filing for a component of its logo.

Justice David Kitchin, the IP specialist in the U.K. Supreme Court, is clearly interested in defensive marks. He decided Ferrero SpA’s Trademarks in 2004,[4] a defensive marks case, when he was an Appointed Person,[5] saying this at the time (about Kinder’s filings):

I believe that the hearing officer was entitled to come to the conclusion that the applicants had established a prima facie case that the registered proprietors did not have a genuine intention to use the marks in issue at the dates they were filed. He was also, in my view, entitled to come to the conclusion that the prima facie case was not answered and that the allegation [of bad faith] was therefore made good.”

He therefore spotted the point quite early on in the development of the law (possibly earlier than anyone) and made it clear that trademarks have to be used as real signs, not just accumulated for their value as legal rights.

While the Sky case may go on to decide what in fact constitutes bad faith in trademark filing, in the author’s opinion, it is unlikely that the case will touch on what is required to be pleaded in order to avoid a bad faith argument being struck out: that point having now been decided by the Court of Appeal in the Tesco case.

Justice Richard Arnold’s decision, overturning judge Joanna Smith at first instance, is of importance in relation to what needs to be pleaded to assert a bad faith claim because it recognizes the fundamental difficulty, at the outset, faced by a party seeking to allege bad faith.

The details of the filing strategy, etc. are initially known only to the mark owner. Therefore, the opponent is unlikely to have any option other than to allege bad faith on the basis of inferences from facts which may later turn out to have a legitimate explanation. Whether or not they do have a legitimate explanation will only become apparent once the mark owner has provided disclosure and evidence and/or has been cross-examined at trial.

Tesco’s bad faith attack is based on entirely orthodox grounds, and if Joanna Smith J’s approach had been correct, it would mean that few, if any, bad faith counterclaims would be able to get off the ground.

The implications of the Tesco case decision for trademark owners are serious. To the extent that they and their advisors may have thought that it was legitimate to file and re-file marks that they are not actually using in order to extend or protect their rights, or avoid the non-use provisions, it is now clear, if ever, there was any doubt, that such a practice is not necessarily legitimate, and may well constitute bad faith trademark filing.

The trial of the action between Lidl and Tesco, where the matter will be finally resolved, is due to take place in February 2023.

Tesco was represented by Simon Malynicz KC of Hogarth Chambers, instructed by Richard Kempner of Haseltine Lake Kempner LLP.

[1] https://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWCA/Civ/2022/1433.html.

[2] Case C-252/12 and [2014] EWCA Civ 1294.

[3] [2021] EWCA Civ 1121.

[4] [2004] RPC 29.

[5] Lord Kitchin at that time (early on in his judicial career) was an Appointed Person, a senior lawyer who is an expert in IP law and authorised to hear appeals from the UK IPO.

Written by Richard Kempner, Solicitor at Haseltine Lake Kempner LLP

| MORE NEWS | | SHARE NEWS WITH OUR EDITOR |