The iconic sneaker brand Nike is locked in a legal battle with Japanese streetwear giant A Bathing Ape (BAPE) over allegations of trademark and trade dress infringement. This lawsuit, filed in January 2023, centers on BAPE’s footwear designs, which Nike claims mimic the protected look and feel of its Air Force 1, Air Jordan 1, and Dunk models.

Understanding trade dress

Trade dress refers to the non-verbal aspects of a product’s presentation, including its design, packaging, and color scheme. It essentially protects the overall image that consumers associate with a particular brand. To qualify for trade dress protection, a design must be:

- Distinctive: It must have acquired distinctiveness in the marketplace, meaning consumers recognize it as belonging to a specific source.

- Non-functional: The design elements cannot be essential to the product’s function.

Nike’s claims

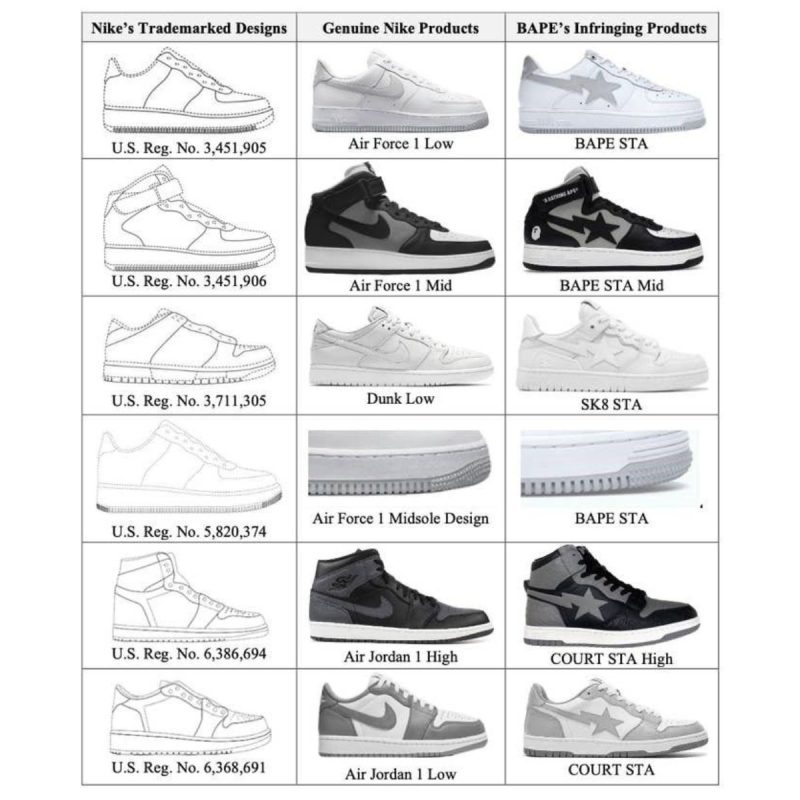

Nike argues that the designs of its Air Force 1, Air Jordan 1, and Dunk lines have achieved trade dress protection through extensive use and consumer recognition. They claim that BAPE’s STA series (STA Mid, SK8 STA, COURT STA High, and COURT STA) are “near verbatim copies” that infringe upon this protected trade dress.

BAPE’s defense

BAPE initially sought to dismiss the case, arguing that Nike’s trade dress claims lacked the necessary legal elements. They contended that the designs in question are too simple to warrant protection and that consumers can easily distinguish between the two brands. In March 2024, the New York Southern District Court dismissed BAPE’s motion, allowing the lawsuit to proceed.

BAPE relies on two cases:

Remy Martin & Co. v. Sire Spirits, 21 Civ. 6838 (SDNY Jan 10, 2022): The legal battle over a cognac bottle design; the court dismissed the plaintiff’s case even though their trademarks were registered. The judge ruled that the complaint lacked a clear list of specific design features the plaintiff claimed were protected.

Heller Inc. v. Design Within Reach, 09 Civ. 1909 (SDNY Aug 14, 2009): The Heller case – which dealt with alleged design infringement of chairs – offers another example. The court rejected the plaintiff’s attempt to use pictures of the chairs as the sole definition of their trade dress. While the complaint included a vague description of the chairs as “ornamental and sculptural,” the court argued that images alone are insufficient. They emphasized the need for a written description that clearly outlines the specific, distinctive features that qualify for trade dress protection. The court also dismissed the plaintiff’s claim that trademark registration eliminates the need to specify the protectable elements of their trade dress.

Judge Gardephe challenged these rulings that required registered trademark owners to prove their trade dress deserved protection under the Lanham Act. They emphasized that courts in his district, including the Second Circuit, have consistently recognized that registration creates an assumption of protection for a trade dress, including its overall design, distinctiveness, and association with the brand.

Case law precedent

The outcome of this case hinges on how the court interprets relevant trademark and trade dress law. Here are some key precedents that could influence the decision:

- Seabrook Test: Established in Seabrook Foods, Inc(568 F.2d 1342C.C.P.A. 1977). This test asks whether the overall impression created by the infringing product is likely to cause confusion with the protected trade dress.

- Secondary Meaning: Courts will consider whether the design elements in question have acquired a “secondary meaning” – i.e., whether consumers associate them specifically with Nike. Cases like Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. v. Samara Brothers, Inc(99-150) 529 U.S. 205 (2000) 165 F.3d120) have explored this concept.

- Inherently Distinctive: In Two Pesos, Inc. v. Taco Cabana, Inc., the Supreme Court held that if a trade dress is inherently distinctive, it can be protectable under § 43(a) without a showing that it has acquired secondary meaning. 505 U.S. at 771, 775 (1992).

The road ahead

The court’s decision to reject BAPE’s dismissal motion paves the way for a full-fledged legal battle. The outcome will hinge on the distinctiveness of Nike’s trade dress and the degree of similarity between the designs.

Nevertheless, trademark infringement cases typically focus on confusingly similar names or logos. However, proving such confusion can be challenging, especially for non-identical marks. This leads to “passing off” claims, where a copycat brand leverages the established brand’s reputation by mimicking its overall look (colors, shapes, designs) to sell its product. Unfortunately, proving “passing off” can be equally tricky.

In the UK’s IP practice cases such as Aldi v. Thatcher (Thatchers Cider Company v Aldi Stores [2024] EWHC 88 (IPEC)), where it is accepted that the words used are so different (THATCHER v. TAURUS) as to confuse, the similarity of the trade dress is emphasized, and in doing so, the distinctiveness of the elements on the packaging is evaluated.

Last but not least, imitation products with various names such as copycat, lookalike, and knock-off have become one of the hot topics in IP practice. Where to draw the line? Whether imitation products are unfair advantage takers that ride the coattail of well-known trademarks or whether they are pivotal actors in the market offering cheap alternatives to the customer, these cases demand a meticulous evaluation from the perspective of the consumer, similar to Judge Melissa Clarke’s approach in the Thatcher decision.

Written by Zeki Emre Kurt

Lawyer, Zek Legal

You may also like…

INTA files statement in intervention in EU case on the inherent distinctiveness of color combination trademarks

New York, New York—July 24, 2024—The International Trademark Association (INTA) has filed a Statement in...

Bytedance stumbles in Singapore: IPOS rejects TIKI trademark challenge

The social media giant Bytedance, owner of the ubiquitous TikTok platform, recently suffered a setback in Singapore....

TOUR DE FRANCE fails in the third stage against German fitness studio chain

At the end of June, the 111th edition of the Tour de France kicked off. June also saw the end of a dispute between...

Contact us to write for out Newsletter