The Australian Federal Court found that Burger King’s Australian franchisee, Hungry Jack’s, engaged in misleading and deceptive conduct for the statement that its BIG JACK burger contained 25% more beef than its well-known rival. However, the Court denied McDonald’s trademark infringement claim that BIG MAC was deceptively similar to BIG JACK.

Background

McDonald’s filed a claim of trademark infringement under s 120(1) of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) against Hungry Jack’s, arguing that Hungry Jack’s had infringed its BIG MAC and MEGA MAC trademarks by using the signs BIG JACK and MEGA JACK. In addition, McDonald’s sought the removal of Hungry Jack’s BIG JACK Australian trademark registration.

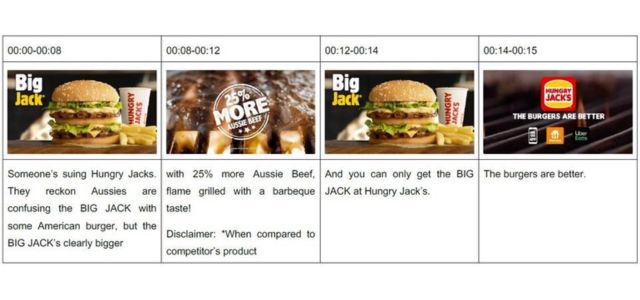

Following the filing of the lawsuit, Hungry Jack’s launched a series of TV advertisements making fun of the lawsuit and claiming its BIG JACK burger was 25% larger than its well-known rival. An example is shown below:

McDonald’s then added a claim that Hungry Jack’s had misrepresented to consumers that its BIG JACK burger contained 25% more beef than the BIG MAC hamburger in breach of s 18 of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL).

Trademark infringement claim

The Court found that the trademarks BIG MAC and MEGA MAC were not deceptively similar to BIG JACK and MEGA JACK, respectively.

- Consumers will give less emphasis to the words “BIG” and “MEGA” because they are descriptive terms. Further, the words “BIG” and “MEGA” are laudatory and many other fast-food chains describe menu items as “BIG.”

- MAC may be perceived as a coined or abbreviated name, but JACK was clearly a common first name.

- “J” and “M” are not similar, and as such, JACK and MAC are visually and phonetically distinct, even though they rhyme.

In evidence, the Chief Marketing Officer of Hungry Jack’s stated that he “was aware that there was an element of cheekiness in naming the product BIG JACK, due to the rhyming of “Jack” and “Mac” in BIG MAC … [and] would likely be perceived as a deliberate taunt of McDonald’s”. Despite this evidence, the Court found that the intention was not to mislead consumers, but only to draw a comparison.

Given the Court found that the marks were not deceptively similar, both McDonald’s trademark infringement claim and its request to cancel Hungry Jack’s registered trademark for BIG JACK were denied.

Misleading and deceptive conduct

Although McDonald’s failed in its trademark infringement claim, it did establish that Hungry Jack’s had engaged in misleading and deceptive conduct in contravention of s 18 of the ACL by claiming that its BIG JACK burger contained 25% more beef than McDonald’s BIG MAC burger.

Key in determining whether Hungry Jack’s was in breach of the ACL was if consumers would understand the statement to be a reference to the uncooked or cooked weight of the patty. Hungry Jack’s argued that the industry standard is to weigh meat by its uncooked weight since different cooking methods will affect the final cooked weight of the meat. In fact, McDonald’s Quarter Pounder burger is a quarter of a pound of uncooked meat (its weight after cooking would be less than a quarter of a pound). Burley J disagreed. Since Hungry Jack’s used images of cooked patties in its advertising, consumers would assume that the BIG JACK was 25% more beef by its cooked weight.

On the evidence, the cooked weight of the BIG JACK beef patty was only around 12.5% – 15.3% larger than the BIG MAC.

Key takeaways

This case was particularly relevant to recent developments in Australian case law with the following key takeaways for the test of “deceptively similar” trademarks:

Reputation is not relevant

Both fast-food chains had a significant reputation in the Australian market. However, earlier this year the Australian High Court resolved in the Self Care case that reputation would not be relevant in assessing deceptive similarity. This was affirmed in McD Asia Pacific LLC v Hungry Jack’s Pty Ltd.

Broader context should not be considered

Hungry Jack’s argued that Self Care was the authority for the position that the court should consider the presence of other marks and colors used on its restaurants in assessing whether the impugned mark is deceptively similar to the registered mark.

Burley J disagreed. Relying on previous case law and distinguishing the facts from those in Self Care, the Court confirmed that only the impugned sign should be considered in assessing deceptive similarity. The broader context of use should not be considered, except as to how goods of the relevant kind are typically bought and sold.

This clarification is not only helpful for trademark infringement cases but also for the examination of trademark applications in Australia.

Written by Natasha Burns

Managing Director, Burns IP

You may also like…

INTA files statement in intervention in EU case on the inherent distinctiveness of color combination trademarks

New York, New York—July 24, 2024—The International Trademark Association (INTA) has filed a Statement in...

Bytedance stumbles in Singapore: IPOS rejects TIKI trademark challenge

The social media giant Bytedance, owner of the ubiquitous TikTok platform, recently suffered a setback in Singapore....

TOUR DE FRANCE fails in the third stage against German fitness studio chain

At the end of June, the 111th edition of the Tour de France kicked off. June also saw the end of a dispute between...

Contact us to write for out Newsletter